I Downloaded a Ps4 and Vita Cross Platform Game but It Asks Me to Buy on Vita Again

Shahid Ahmad nearly passed out in the eye of 1 of the well-nigh of import conversations of his professional person life.

It was a Friday night in late 2011, around 7:30 p.yard. Ahmad, the managing director of strategic content at Sony Estimator Entertainment Europe, was approaching his 12th hr of work, and he'd been on and off the telephone all day, doing his part to save PlayStation.

In those days, Sony was in the midst of something approaching turmoil. The PlayStation 3 was winding downwardly, and its successor was years away from being unveiled. Sony's second handheld, the PlayStation Vita, was due to launch tardily that year in Japan and early the following year in the Americas and Europe. Its first handheld, the PSP, was a moderate seller at a time when its straight, dual-screened competition at Nintendo was finding enormous sales success.

PlayStation needed a win. It needed something new, and Ahmad was function of the programme to deliver that. It would have to begin equally an act of, if not agony, then one built-in of a company that had seen better days. And if information technology worked, there was the possibility of an even bolder plan. And that clandestine new program was his idea.

But that was for afterwards. Today, Ahmad was on the phone because he'd recently switched roles within of SCEE. His new task was all about convincing developers to create or bring their existing games to Sony's platforms using the nascent PlayStation Mobile proposal. His task was to convince game makers to join a programme that would allow them to create games using a PlayStation framework. Gamers could then play the games they made (or ported) on sure Android phones and PlayStation Vita.

The goal's upsides were buttressed past a major problem, though: Selling PlayStation to developers, let alone on new initiatives and unproven platforms, wasn't as easy equally it once was. Sony was trailing its competitors at Microsoft and Nintendo. And it had been for years.

Shahid Ahmad

Shahid Ahmad

Gone were the days of PlayStation ii, where Sony reigned supreme in the panel market. Instead, Sony overshot with the PlayStation 3'due south high initial price and its newfangled and circuitous Cell processor hardware. As a result, Sony — which had once been a disrupting titan — had spent the previous few years communicable up with competition that had beaten it to market and at the greenbacks register.

Shahid Ahmad knew this, and his new task was an acquittance of that reality. In late 2011, his part was to convince developers that Sony and PlayStation were skilful investments worthy of the time and try it would accept to bring their games to these new platforms.

Ahmad and the strategic content team had about six months before the applied science shipped, and went into "full-on sales mode," he says.

And and so, on a Friday evening in late 2011, he connected with Rami Ismail of the independent development studio Vlambeer. If an indie developer can be a stone star, Ismail is one of the most famous front end men. He is public, outspoken and well-known. And if Vlambeer agreed to port its popular games, Ahmad thought that could create valuable momentum in the budding PlayStation Mobile platform.

Lonely in the function and on a monumentally of import telephone call with Ismail, Ahmad's Type 1 diabetes asserted itself with prejudice. He had what he calls a "full-on hypoglycemic attack."

"Like a fool," Ahmad tells Polygon, "I carried on talking, but I didn't know what I was saying. Considering at this indicate, I started to feel similar I was going to blackness out."

He struggles to call up what followed through the haze of a years and shock. He remembers the function refrigerator. He remembers an empty Coke that he doesn't remember drinking. And he remembers that Ismail didn't say anything out of the ordinary, which he thinks ways that the attack went unnoticed.

Foolish or not, his force of will worked. A phone telephone call that could take resulted in disaster instead ended in "the get-go of a cute relationship," he says. Vlambeer's Super Crate Box appeared as i of almost thirty games when PlayStation Mobile launched roughly six months later.

"At this indicate, I started to feel similar I was going to blackness out."

Since its release almost four years ago, the PS Vita has been, similar its predecessor, a mixed bag for Sony. It was never an overwhelming sales success, nor was it burdened with a long list of exclusive games. But it has survived with a adequately steady stream of releases to continue the handheld viable as a platform. It even gained a bit of new life with the release of the PlayStation 4 in late 2013. But its future — and even the future of handheld gaming at Sony — is less than assured.

Just terminal calendar month, Shuhei Yoshida, the worldwide studios chief for Sony Computer Amusement, told a panel that "the climate is not healthy" for a PS Vita successor. Blame Android and iOS. Then, a few days agone, a PlayStation executive said that Sony'south get-go-party studios have "no titles in development for PS Vita."

Neither of those things audio adept separately. Together, they paint a dreary picture show for the handheld. At to the lowest degree right at present, Sony's game makers have abandoned the PlayStation Vita. The handheld could exist entering the final phases of its life without any viable offspring, as the company concentrates on its hit hardware, the PS4.

Whether that makes the PS Vita a failure is a separate upshot. The handheld has been beleaguered from the start, and it never quite managed to establish itself as a platform for launching new, exclusive games. But in the years since the PS Vita's release, any success that Sony can brag almost owes a lot to one man's ideas. And those ideas do non stop at the PS Vita.

In late 2011, Shahid Ahmad wasn't going to permit Type 1 diabetes cease his conversation with Rami Ismail whatever more than he was going to let PlayStation'south bug stop his quest to reverse the course of Sony's slide. Sony needed games, which meant it needed developers. And he had a program to get them. He just had to convince his bosses at Sony to let him do something kind of weird starting time.

A Developer AT Center

Shahid Ahmad didn't set out to be an evangelist for a platform or a well-known developer's assistant. He set out to brand games. He published his first for the Atari 400 in 1982. The young programmer fabricated a cassette tape and advertised in magazines. He sold zero copies.

Thirty years later, that story holds a lesson that he inserts into his daily life: If nobody knows about what you make, that'due south a huge problem. Information technology doesn't matter how difficult you worked or how skillful it is if it disappears into the atmosphere.

"It was ahead of its time, in some ways, which means failure, of course."

Throughout the ensuing years, Ahmad kept making games and, eventually, started helping others make them. He worked equally a developer for more than a decade, so moved into the publishing side at Virgin Publishing and Hasbro Interactive, where he helped reboot the Atari brand in the early on 2000s.

So he realized that there was some other way he could make a contribution on his own, and so he founded a company chosen Outset Games.

The concept was straightforward: Start would help game makers with their pitches to publishers and console makers. These were the days before the independent developer revolution, when the walled gardens of consoles were much higher than they are today. Start would live in the heart, helping games become where their creators wanted them to go. When successful, Get-go receive some portion of the game's acquirement.

Beginning had some success until its funding was unceremoniously pulled.

"It was ahead of its time, in some ways, which means failure, of course," Ahmad says with a laugh.

Tossed into turmoil, his company gone, Ahmad had what he calls a "life implosion." He had to figure out what was side by side. And the answer was consoles and Sony. He joined the company's developer relations division at just about the time that Sony and PlayStation'south fortunes were shifting.

A TOUGH CELL

Many at Sony believed they would ride the high from the PS2 to the newest console, the PlayStation 3. They were wrong.

Sony poured its considerable might into its next-generation system, which information technology revealed in 2005. Its core was built around the Cell microprocessor. It was powerful and cutting edge, and Sony believed its benefits were self-evident. And non just in video game consoles. Its extensibility, Sony's thinking went, extended to common household appliances like refrigerators and fifty-fifty televisions. But before all that, there was the PlayStation 3, powered by the powerful new Jail cell technology.

Unfortunately for Sony, the Jail cell processor gained a reputation for being difficult to plan for. That coupled with the rise in popularity of Microsoft'southward Xbox 360, which was released more than than a twelvemonth before the PS3, many developers used Microsoft'due south system every bit a lead and ported their games to PS3. Further, many multi-platform developers and publishers didn't encounter the benefit of spending inordinate amounts of fourth dimension to make a multiplatform game look spectacular on organisation and not the other. Once they got comfortable with the PS3 they could brand games that looked just as good on both.

By the time that Ahmad joined Sony, it was years into this hard and unexpected catamenia. Sony wasn't failing, exactly, simply it couldn't be described as winning, either.

And Sony knew it. What might one time have been described as arrogance built-in of the PS2's success became something like humility, as Sony recognized that developers didn't flock to the PS3. Instead, Sony had to convince many of them to join. And a sense of contrite humility wasn't going to be plenty.

The polices that existed within Sony for dealing and negotiating with developers and publishers were designed when Sony was a powerful leader of the industry and based on a time when things worked differently. At this indicate, both were relics. In fact, many believed those policies were hurting Sony, though not everyone inside the company agreed.

Enter Ahmad, who used his experience and contacts to create a lineup for a company that was now unveiling a new way to play games — PlayStation Mobile — on new devices.

That would turn out to be something that he became very adept at over the next few years.

A HANDHELD WITHOUT GAMES

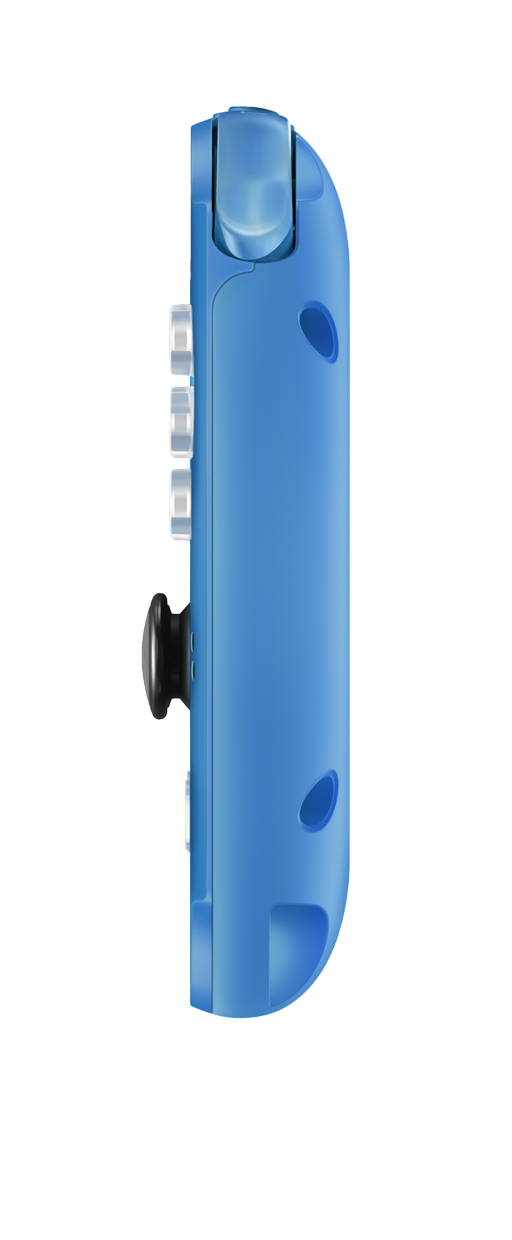

When Sony unveiled the PlayStation Vita, the hardware fabricated sense.

It was created in an era after the iPhone ushered in the mobile gaming revolution, and Sony'south PSP successor incorporated much of the technology that underpinned Android and iOS smartphones and tablets. Just it was more than than that, also.

Sony surrounded the PS Vita'due south touchscreen with a rear touchpad and physical buttons and dual analog sticks. The message was articulate: This new device was designed to capture the all-time of the console and smartphone worlds. Game makers could create console-like experiences for it, without forcing gamers to use their fingers to smudge their screens and wrestle with imprecise controls. The idea seemed to be, to crib a line from Field of Dreams, that if yous built it, they would come.

They did. Simply not many.

"Established players weren't bringing content to Vita."

The problem, as Sony would shortly notice out, was that some of the biggest developers and publishers weren't convinced that the new device was worth the investment, in part considering "the install base just wasn't in that location," Ahmad says. Information technology's not that the Vita didn't accept games or players. Information technology only didn't have as many as Sony or game makers might have expected, and the "established players weren't bringing content to Vita."

It was, by now, an achingly familiar state of affairs. Sony infused its new handheld with technology that made portable gaming popular, surrounded by the solid design that made console gaming popular. But just equally the PS3 struggled to win developers, then did the PS Vita.

Things were going badly again, but this time, Sony didn't accept to await years to figure out what to do. Thanks to PlayStation Mobile, some of those inside of SCEE already proved they could plant relationships with games makers and convince them to spend their time and money on nascent platforms like PlayStation Mobile. And if Ahmad and his team could help with those, the thinking went, maybe they could assist with the struggling handheld, also.

When Sony'due south PS Vita bug emerged, he best-selling, for example, that the world had changed. At Sony, that meant acknowledging that panel makers don't wield the ability they once did — and that information technology had to modify to reverberate this new reality. Sony could blame the various app stores, the rise of digital distribution services similar Steam, the power for small, independent publishers to forgo consoles entirely if need be. It also needed to acknowledge that its attitude needed to change, also.

THE NEW Earth Lodge

Like Jurassic Park'south dinosaurs, consoles used to rule the world.

They were never lone, of grade. PC gaming has been alive and well longer than consoles. Only PC gaming has always been a fleck more hardcore and required more investment. Tracing their style through Atari and the NES, consoles had long been the most mainstream manner for nearly people to play video games. And, later a famously failed relationship with Nintendo, Sony got in on the action. Enormous success followed.

For the offset few decades of video game consoles, platform creators were more often than not very picky most who and what ended upwardly on their hardware, and that made panel gaming an expensive suggestion for developers. But the ascension of services similar Steam made PC gaming distribution easier. It streamlined and managed the complexities — and it made getting games on the platform easier for those who fabricated games.

Information technology wasn't that Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony were less popular by the 2nd decade of the 21st century. Consoles were more popular than ever, at least in terms of sales figures. Merely contest made them less powerful, less able to need strict terms from those who appeared on their platforms and less able to counterbalance their contracts heavily in favor of publisher rights. Information technology wasn't enough to build the best hardware. Companies also had to build the best policies to concenter developers to their ecosystems.

Now, Sony had a new platform in a new era, but its thinking was out of appointment, at to the lowest degree according to Ahmad. At first, Sony banked on the traditional method of attracting games to the PS Vita, just the games weren't coming, despite Sony'southward efforts.

"Commercially, would you want to do that?" he asks nearly big-name publishers bringing games to the handheld. "Why would you want to create content for a platform that's not going to support you lot commercially? And what I mean is, in terms of throwing millions and millions and millions of dollars at something, knowing that in that location'south not the market at that place to recoup that."

Out of that agreement came a career-defining revelation: In that location is a group of game makers who don't suffer nether those burdens or restrictions. They are the very content creators who took reward of the plummeting costs of game evolution and thrived in app stores. If he was right, then Sony didn't have to give up on its onetime partners. But perchance it could salve the PS Vita by acknowledging that there was an opportunity to court new partners.

Shahid Ahmad had a plan. Now he only had to convince Sony to follow it.

"What I decided to do was pitch to executive management a plan to bring a whole bunch of contained developers to Vita," he says. "And the reply, surprisingly, was yes."

A couple of early wins showed that Ahmad'southward plan had merit. Outset was developer Sports Interactive's Football Manager Classic, a version of the long-running sports management simulator. As a harbinger of things to come up, Ahmad took to Twitter and asked what players would like to see on Vita. The top answer was Namco'due south Tales Studio's Tales of Heart R. It wasn't an indie game or a small company, just it soon came to the system.

It wasn't all successes, but the program was outset to produce results. A couple of unanswered questions remained, though. Could Sony keep to courtroom developers like these? And would doing and then have an bear on on the PlayStation Vita?

SUSTAINABILITY THROUGH HUMANITY

The early successes were promising, but there was no guarantee that Ahmad's strategy would last. This didn't not take hold of him unaware. In fact, he prepared for information technology nether an aggressive plan to bring 55 games to the platform in almost 18 months.

Ahmad wasn't just courting game makers by throwing around Sony'southward considerable might. He was changing how Sony idea virtually getting games on its systems and establishing what he hoped would exist long-lasting, equitable relationships with the human being beings who wanted their games on Sony'due south hardware and the human beings who wanted games to play on the systems they owned. That's why social media became such an integral part of his strategy.

"I caused people to freak out when I was on Twitter to begin with," he says. "And I can understand why. I hadn't sought anybody's permission for it — and I'll probably get shot for proverb that. I certainly tried to be as conscientious as I could, but in gild to display some congruence, it was very of import for me to be reasonably open up on Twitter. And that helped enormously. Information technology made a really, really big difference."

For platform owners like Sony, there are always two distinct groups that demand satisfaction: the consumers who buy hardware and software and the developers and publishers who create and fund content for that hardware. The common denominator, Ahmad realized, is their humanity — a flowery term with practical implications.

In short, he believes that there's a danger in failing to acknowledge humanity, a danger that Sony and other platform owners once inadvertently courted. Ahmad's programme, in part, was to focus interaction with everyone on a personal level.

"People respect that openness," he says. "They see that you're a human being, that you're non just reciting a company mantra. Simply the of import thing is, equally long as you stay on rails and in line with the company values, you're usually OK."

In curt, when he courted developers, he was trying to solve a trouble of perception, whether perceived rightly or wrongly, for both sides by injecting humanity in to the word. When applied to game makers, presenting what he calls a "visitor front," which is necessarily devoid of much humanity, sends a message that those you're talking to should also present their best company front. But when you approach them from a different angle — using the aforementioned company values, but treating your interactions differently — you end fostering defensiveness.

"With people, that takes a lot less time," he says.

None of this is to say that Sony is suddenly all feelings and flowers and doesn't care about its interests or shareholder value. Those are still company values. They just don't take to be at the forefront of every discussion. Ahmad thought Sony could and should build relationships based not merely on corporate interests or bottom lines but on their shared love of the industry and their desire to spread games far and wide. There's more than one manner to court a developer, and he'south out to bear witness it.

Bending THE RULES

Ahmad made his pitch and received approval. At present his job was to back the theory up and bring games to the PlayStation Vita. He started by bending the rules.

"One of the things I asked for was carte blanche to ride barbarous over some of the existing policies," he says. "And executive management, to their immense credit, gave me the flexibility that I needed."

He and his team focused on being "extremely developer friendly," he said. Ahmad thinks his team's departure from longstanding policies must have frustrated some inside Sony, but he believes many also understood that there was a higher purpose to existence "really absurd" with independent developers.

It wasn't a popularity contest, in other words. Competition was part of the equation, besides.

"The way I put information technology to the squad was really rather dramatic," he says. "I said, 'The patient'south having a heart assail. Nosotros need to do open up heart surgery at present. Nosotros don't accept time to sit effectually and discuss this for months on end.'

"I gauge I was being a little bit rude past saying that. Simply actually, we just needed to make that decision very chop-chop, and to their immense credit, they gave the become-ahead."

The PS Vita was arguably failing, and that meant that Sony was more willing to heed to radical ideas. Ahmad'south program wasn't about courtship established companies. It was about talking to people who'd never fabricated anything for PlayStation before. That'southward why he idea he had to be so dramatic in his presentation: to impress upon them the necessity of this oddity.

It worked. Ahmad and his team went after cool games and cool developers. They built relationships. They asked fans what they wanted. They listened. They're like Sony'due south version of record industry A&R employees. They're out at that place listening to bands, trying to sign the best of them. And they continue to practise so.

The showtime mission was to make certain that developers even knew that they could bring their games to Sony's systems, which wasn't a given. Ahmad wanted to change the perception and permit developers know that they're welcome on systems similar the PS Vita. And that goes back to establishing a personal relationship.

"People similar to practise business with people that they like," he says. "Information technology's only easier. It's nicer. Why present a corporate front? Simply exist a human existence."

COURTING INNOVATION

At first, the central idea may have been mostly about getting games on the Vita, but over time, contained developer innovation became another benefit of the strategy. And that strategy wasn't bound to Sony's handheld. The benefits of becoming more than developer friendly also applied to other hardware, like the PlayStation 4.

Now that the word is out and Sony doesn't have to spend so much time convincing developers to bring together its ecosystem, these days, instead of simply looking for developers and games, Ahmad is looking for innovation. It'due south no surprise that he counts Hello Games' No Homo's Sky as a recent win. The game will make its console debut on the PS4.

Of course, Sony wants big AAA developers on its platforms. That is an of import role of the concern. But it's no longer the only part of the business concern — or, maybe, fifty-fifty the focal signal. With the resounding success of the PS4 — the showtime piece of hardware Sony produced in quite a long time that became an firsthand and unequivocal hitting — Sony'southward job is becoming a bit easier.

Ahmad loves AAA games. He plays many of them. He doesn't believe that indie games are meliorate than AAA games. "That would be absurd," he says. And he'south not even saying that he blames AAA developers for beingness, on the whole, less innovative than their indie counterparts. Franchises pay salaries, and that's a totally understandable and valid way to satisfy players and sustain a business organization, something he thinks it'due south important to "award and respect."

1 way he sees as proof that his strategy worked is that it's non just nearly finding developers anymore. Developers now arroyo Sony.

He seems to have inspired a bit of humility in Sony, too. Of course, Sony offers incentives for exclusivity, but it doesn't "need it," he says. "In that location'due south no formal requirement for you to launch your game on PlayStation starting time — or even at the same time." That's good for everyone involved, he maintains, considering the old developer believes that game makers are the lifeblood of the industry. Making Sony's platforms more developer friendly helps anybody.

Ahmad'south job is to convince players and games makers that people go to Sony devices to play games. Developers make games. Sony makes devices to play those games. If both sides sell their production — and Sony tin can help them do that past featuring their game in its digital storefronts — then everybody wins.

But even if everybody wins, that doesn't hateful that everybody'south happy. Even though Ahmad's boldness made the PlayStation Vita more valuable, the simple truth is that the handheld still isn't a resounding success. And Yoshida's contempo comments are an acknowledgement of that reality. Then is the recent news nigh no start-party titles being in evolution for the handheld.

This shouldn't come equally a surprise. Shuhei Yoshida told Polygon at E3 2015 that independant developers and third-party games are increasingly becoming the handheld'southward focus.

"It's very fortunate that the indie boom happened and they are providing lots of great content to Vita," Yoshida told Polygon in June. "Gameplay, game mechanic wise, people want to spend 10 minutes, xv minutes getting in and out. On Vita, it's swell with suspended functionality, and then these indie games really great for that from a game design standpoint.

"Instead of watching big stories or cine, you can spend hours on Vita. So, I think that's actually the biggest star to aid provide nifty content to Vita going forward. And we continue to make games cross-platform games, especially on digital side."

Shahid Ahmad may have breathed new life into the Vita and brought more software from more than diverse developers, but its future remains uncertain. It could be that PlayStation four and its growing listing of independent developers is the real casher of Ahmad'southward radical humanity.

Courting HAPPINESS

PlayStation is a business, once huge, one time smaller, now huge again. Just as PlayStation Vita had to get small before it got bigger, and so did PlayStation as a whole. And Ahmad is proud of the work he'south done.

"We gave Vita another lease on life by giving information technology a different direction," he says. "Information technology was effectively a reboot. And it worked."

People used to complain that Vita didn't accept games. That'due south a harder argument to sustain these days. Though people aren't always happy what arrives on the handheld — it's often a lot of games that came out somewhere else first — y'all don't hear most the platform'south dearth of games and then much anymore.

The PlayStation Vita may not exist the breastwork for for AAA game developers or Japanese office-playing games that people want, just information technology was never likely to be. Instead, it has become a platform where newcomers thrive. The reboot that Ahmad and his squad engineered transformed the struggling system into something more successful than information technology was when it began. And games like Fez, Spelunky, Hotline Miami, OlliOlli and others seem to accept convinced owners that indie development is something to be embraced.

"I'one thousand not saying everyone," Ahmad says. "There are still a lot of fans out in that location who want the AAA, only commercial realities make that pretty hard."

The Vita's integration with the PS4 only increases its value, besides. Destiny may non get a native Vita release, just yous can play it on your handheld system under sure, not overly crushing weather condition.

Yes, these days in the popular consciousness and even at Sony, the PS4 has become the gilded kid. Whatsoever the PS Vita's future, its past and whatever degree of success it attained is inextricably linked with Ahmad.

Though systems may alter, Ahmad's focus and strategy remain the aforementioned. He insists on meeting those he interacts with on a fundamentally personal level. It'southward adept for business, he thinks. It'southward good for life, too.

"It'due south merely adept to be good," he says.

Of grade, Ahmad wouldn't accept been able to do any of this if his superiors at Sony hadn't been willing to alter. And they would most certainly take been less willing to practise so if Sony had maintained its PS2-era momentum. Ultimately, Ahmad's story is an acknowledgement that the earth had moved on and Sony had to adapt or settle. It chose to adapt.

All this talk of humanity makes it an piece of cake target for cynicism, but to hear Shahid Ahmad discuss information technology, it sounds equally logical as information technology does sincere. Sony runs a business with clients. Ahmad and Sony desire to make clients happy. And his crazy, radical proposition was that he could practice that on a more human level and work his socks off to make sure they remained happy.

Success, they figured, would follow. They weren't wrong.

"The earth had changed," Shahid Ahmad says. "The of import thing was, nosotros had to change forth with it."

Source: https://www.polygon.com/features/2015/10/29/9409697/playstation-vita-successor-changed-sony-shahid-ahmad-ps4

0 Response to "I Downloaded a Ps4 and Vita Cross Platform Game but It Asks Me to Buy on Vita Again"

Post a Comment